First Postmaster General of the United States

Signer of the Declaration of Independence

Signer of the Declaration of Independence

U.S. Paris Peace Commissioner 1776-1784

Signer of the US Constitution of 1787

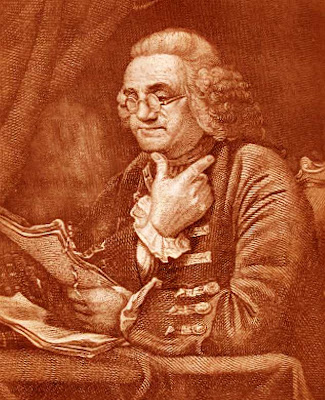

Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706 – April 17, 1790) was one a signer of the US Constitution of 1787, Declaration of Independence, and Paris Peace Commission. He was the first US Postmaster General, a major figure in the American Enlightenment and scientist. He facilitated and/or founded many civic organizations, the American Philosophical Society, Union Fire Company, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Contributionship Insurance Company, and the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery.

FRANKLIN, Benjamin, statesman and philosopher, born in Boston, Massachusetts, 17 January 1706 and died in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 17 April 1790. His family had lived for at least three centuries in the Parish of Ecton, Northamptonshire, England, on a freehold of about thirty acres. For several generations the head of the family seems to have been the village blacksmith, the eldest son being always inheriting the family business.

Benjamin's grandfather, Thomas, born in 1598, removed late in life to Banbury, in Oxfordshire, while his eldest son, Thomas, remained on the estate at Ecton. Thomas Franklin received a good education, and became a scrivener. He became one of the most prominent men in his County, and formed a friendship with the Earl of Halifax. He is said to have borne a strong likeness to Benjamin Franklin, his nephew.

The second son, John Franklin, was a dyer of

woolens, and lived in Banbury. The third son, Benjamin, for some time a silk

dyer in London, immigrated to Boston at an advanced age, and left descendants

there. He took a great interest in politics, was fond of writing verses, and

invented a system of shorthand. The fourth son, Josiah, born in 1655, served an

apprenticeship with his brother John, at Banbury, but removed to New England in

1682. From the beginning of the Reformation the family had been zealous

Protestants, and in Mary's reign had incurred considerable danger on that

account. Their inclination seems to have been toward Puritanism, but they

remained in the Church of England until late in the reign of Charles II, when

so many clergymen were dispossessed of their holdings for nonconformity, and

proceeded to carry on religious services in conventiclers forbidden by law.

Among these dispossessed clergymen in Northamptonshire were friends of Benjamin

and Josiah, who became their warm adherents and attended their conventiclers.

The persecution of these nonconformists led to a

small Puritan migration to New England, in which Josiah took part. He settled

in Boston, where he followed the business of soap boiler and tallow chandler.

He was twice married, the second time to the daughter of Peter Folger, one of

the earliest settlers of New England, a man of some learning, a writer of

political verses, and a zealous opponent of the persecution of the Quakers. By

his first wife Josiah Franklin had seven children; by his second, ten, of whom

the illustrious Benjamin was the youngest son. For five generations Benjamin Franklin’s

direct ancestors had been youngest sons of youngest sons.

At the age of ten, after little more than a year at

the grammar school, Benjamin was set to work in his father's shop, cutting

wicks and filling molds for candles. Benjamin, bored with the job, became an

insatiable reader, and the few shillings that found their way into his hands

were all laid out in books. His father thought of sending him to Harvard and

educating him for the ministry but the family finances of such a large family

proved inadequate for the tuition.

Franklin began to show symptoms of a desire to run

away and go to sea. To turn his mind from this, his father at length decided to

make him a printer. His elder brother,

James, had learned the printer's trade, and in 1717 returned from England with

a press, and established himself in business in Boston.

Franklin wrote little ballads and songs of the

chapbook sort, and peddled them about the Streets, sometimes with profit to his

pocket. He also read Shaftesbury and Collins, which strengthened an inborn

tendency toward freethinking.

In 1721 James Franklin began printing and publishing

the "New England Conrant," the third newspaper that

appeared in Boston, and the fourth in America. For this paper Benjamin wrote

anonymous articles, and contrived to smuggle them into its columns without his

brother's knowledge of their authorship; some of them attracted attention, and

were attributed to various men of eminence in the colony. The newspaper was

quite independent in its tone, and for a political article that gave offence to

the colonial legislature James Franklin was put into jail for a month, while

Benjamin was duly admonished and threatened. Finding himself somewhat unpopular

in Boston, and being harshly treated by his brother, whose violent temper he

confesses to have sometimes provoked by his sauciness, Benjamin at length made

up his mind to run away from home and seek his fortune.

![National Collegiate Honor’s Council Partners in the Park Independence Hall Class of 2017 at the Benjamin Franklin Museum. Sophia Semensky is holding an American Museum Magazine or Repository of Ancient and Modern Fugitive Pieces, &c., No. 5 May, 1787 [second edition, 1789], Published by Mathew Carey, Philadelphia. This issue include the full printing of The Constitution of the Pennsylvania Society, for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and the Relief of Free Negroes, Unlawfully Held in Bondage: begun in the year 1774, and enlarged on the twenty-third of April, 1787. Signed type Benjamin Franklin, President. This Pamphlet was gifted to Independence Hall National Historic Park by Stanley and Naomi Yavneh Klos. - http://www.historic.us/p/nchc-partners-in-park.html](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhoVCocjShCSdx33OFrGuNIrPr-VqdGUjaKPyMwqtBWx7Rb-H0COe60PbskehOWDyn8HKjlIDil4eeNmn23XKRgxfsFgWFTwOI6PvR4fAAvJtMqB3GzmMv9zg9K1qmVYTN3UApssSM-5ev3/s640/NCHC+Citizenship+PITP+Franklin+Museum+-+Slavery+Abolition+Gift.png) |

National Collegiate Honor’s Council Partners in the Park Independence Hall Class of 2017 at the Benjamin Franklin Museum. Sophia Semensky is holding an American Museum Magazine or Repository of Ancient and Modern Fugitive Pieces, &c., No. 5 May, 1787 [second edition, 1789], Published by Mathew Carey, Philadelphia. This issue include the full printing of The Constitution of the Pennsylvania Society, for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and the Relief of Free Negroes, Unlawfully Held in Bondage: begun in the year 1774, and enlarged on the twenty-third of April, 1787. Signed type Benjamin Franklin, President. This Pamphlet was gifted to Independence Hall National Historic Park by Stanley and Naomi Yavneh Klos. - For More information please visit NCHC Partners in the Park 2017 |

He raised a little money by selling some of his

books, and in October 1723, set sail in a sloop for New York. Unable to find

employment there as a printer, he set out for Philadelphia, crossing to Amboy

in a small vessel, which was driven upon the coast of Long Island in a heavy

gale. Narrowly escaping shipwreck, he at length reached Amboy in the crazy

little craft, after thirty hours without food or drink, except a drop from a

flask of what he called "filthy rum." From Amboy he

made his way on foot across New Jersey to Burlington, whence he was taken in a

rowboat to Philadelphia, landing there on a Sunday morning, cold, bedraggled,

and friendless, with one Dutch dollar in his pocket. But he soon found

employment in a printing office, earned a little money, made a few friends, and

took comfortable lodgings in the house of a

Mr. Read, with whose daughter Deborah he proceeded to fall in love.

It was not long before his excellent training and

rare good sense attracted the favorable notice of Sir William Keith, governor

of Pennsylvania. The Philadelphia printers being ignorant and unskillful, Keith

wished to secure Franklin's services, and offered to help set him up in

business for himself and give him the government printing, such as it was.

Franklin had now been seven months in Philadelphia, and, his family having at

length heard news of him, it was thought best that he should return to Boston

and solicit aid from his father in setting up a press in Philadelphia. On

reaching Boston he found his brother sullen and resentful, but his father

received him kindly. He refused the desired assistance, on the groined that a

boy of eighteen was not fit to manage a business, but he commended his industry

and perseverance, and made no objection to his returning to Philadelphia,

warning him to restrain his inclination to write lampoons and satires, and

holding out hopes of aid in ease he should behave industriously and frugally until

twenty-one years of age.

On Franklin's return to Philadelphia, the governor

promised to furnish the money needful for establishing him in business, and

encouraged him to go over to London, in order to buy a press and type and

gather useful information. But Sir William was one of those social nuisances

that are lavish in promises but scanty in performance. It was with the

assurance that the ship's mailbag carried letters of introduction and the

necessary letter of credit that young Franklin crossed the ocean. On reaching

England, he found that Keith had deceived him. Having neither money nor credit

wherewith to accomplish the purpose of his journey or return to America, he

sought and soon found a place as journeyman in a London printing house. Before

leaving home he had been betrothed to Miss Read. He now wrote to her that it

would be long before he should, return to America.

His ability and diligence enabled him to earn money

quickly, but for a while he was carried away by the fascinations of a great

City, and spent his money as fast as he earned it. In the course of his

eighteen months in London he gained much knowledge of the world, and became

acquainted with some distinguished persons, among others Dr. Mandeville and Sir

Hans Sloane; and he speaks of his "extreme desire" to

meet Sir Isaac Newton, in which

he was not gratified. In the autumn of 1726 he made his way back to

Philadelphia, and after some further vicissitudes was at length (in 1729)

established in business as a printer.

He now became editor and proprietor of the "Pennsylvania

Gazette," and soon made it so popular by his ably written

articles that it yielded him a comfortable income. During his absence in

England, Miss Read, hearing nothing from him after his first letter, had

supposed that he had grown tired of her. In her chagrin she married a worthless

knave, who treated her cruelly, and soon ran away to the West Indies, where he

died. Franklin found her overwhelmed with distress and mortification, for which

he felt himself to be partly responsible. Their old affection speedily revived,

and on I September 1730, they were married. They lived most happily together

until her death, 19 December 1774.

As Franklin grew to maturity he became noted for his

public spirit and an interest at once wide and keen in human affairs. Soon

after his return from England he established a debating society, called

the "Junto," for the discussion of questions in

morals, politics, and natural philosophy. Among the earliest members may be

observed the name of the eminent mathematician, Thomas Godfrey, who soon

afterward invented a quadrant similar to Hadley's. For many years Franklin was

the life of this club, which in 1743 was developed into the American philosophical

society.

In 1732 he began publishing an almanac for the

diffusion of useful information among the people. Published under the pen name

of " Richard Saunders," this entertaining collection

of wit and wisdom, couched in quaint and pithy language, had an immense sale,

and became famous throughout the world as " Poor Richard's

Almanac." In 1731 Franklin founded the Philadelphia library. In

1743 he projected the University that a few years later was developed into the

University of Pennsylvania, and was for a long time considered one of the

foremost institutions of learning in this country.

From early youth Franklin was interested in seined title

studies, and his name by and by became associated with a very useful domestic

invention, and also with one of the most remarkable scientific discoveries of

the 18th century. In 1742 he invented the "open stove, for the

better warming of rooms," an invention that has not yet entirely

fallen into disuse. Ten years later, by wonderfully simple experiments with a

kite, he showed that lightning is a discharge of electricity; and in 1753 he

received the Copley medal

from the Royal society for this most brilliant and pregnant discovery.

A man so public-spirited as Franklin, and editor of

a prominent newspaper besides, could not long remain outside of active

political life. In 1736 he was made clerk of the assembly of Pennsylvania, and

in 1737 postmaster of Philadelphia. Under his skillful management this town

became the center of the whole postal system of the colonies, and in 1753 he

was made deputy postmaster general for the continent. Besides vastly increasing

the efficiency of the postal service, he succeeded at the same time in making

it profitable. In 1754 Franklin becomes a conspicuous figure in Continental

politics. In that year the prospect of war with the French led several of the

royal governors to call for a congress of all the colonies, to be held at

Albany. The primary purpose of the meeting was to make sure of the friendship

of the Six Nations, and to organize a general scheme of operations against the

French. The secondary purpose was to prepare some plan of confederation that

all the colonies might be persuaded to adopt. Only the four New England

colonies, with New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, sent commissioners to this

congress. The people seem to have felt very little interest in the movement.

Among the newspapers none seem to have favored it warmly except the "Pennsylvania

Gazette," which appeared with a union device and the motto "Unite

or Die!"

At the Albany congress Franklin brought forward the

first coherent scheme ever propounded for securing a permanent Federal union of

the thirteen colonies. The plan contemplated the union of the colonies under a

single central government, under which each colony might preserve its local

independence. The legislative assembly of each colony was to choose, once in

three years, representatives to attend a Federal grand council, which was to

meet every year at Philadelphia, as the City most convenient of access from

north and south alike. This grand council was to choose its own speaker, and

could neither be dissolved nor prorogued except by its own consent, or by

especial order of the crown. The grand council was to make treaties with the

Indians, and regulate trade with them; and it was to have sole power of

legislation on all matters concerning the colonies as a whole. To these ends it

could lay taxes, enlist soldiers, build forts, and nominate civil officers. Its

laws were to be submitted to the king for approval; and the royal veto, in

order to be effective, must be exercised within three years. To this grand

council each colony was to send a number of representatives, proportioned to

its contributions to the continental military service, the minimum number being

two, and the maximum seven. With the exception of such matters of general

concern as were to be managed by the grand council, each colony was to retain

its powers of legislation intact. In an emergency any colony might singly

defend itself against foreign attack, and the Federal government was prohibited

from impressing soldiers or seamen without the consent of the local

legislature. The supreme executive power was to be vested in a president or

governor general, appointed and paid by the crown. He was to have a veto on all

the acts of the grand council, and was to nominate all military officers,

subject to its approval. No money could be issued save by joint order of the

governor general and council. "This plan," said

Franklin, "is not altogether to my mind; but it is as I could get

it."

To the credit of its great author, it should be

observed that this scheme long afterward known as the "Albany plan

"contemplated the formation of a self-sustaining Federal government, and

not of a mere league. It aimed at creating "a public authority as

obligatory in its sphere as the local governments were in their spheres";

and in this respect it was much more complete than the Articles of Confederation under

which the thirteen states contrived to live from 1781 till 1789. But public

opinion was not yet ripe for the adoption of such bold and comprehensive ideas.

After long debate, the Albany congress decided to adopt Franklin's plan, and

copies of it were sent to all the colonies for their consideration; but nowhere

did it meet with popular approval. A town meeting in Boston denounced it as

subversive of liberty; Pennsylvania rejected it without a word of discussion;

not one of the assemblies voted to adopt it. When sent over to England, to be

inspected by the ministers of the crown, it only irritated them. In England it

was thought to give too much independence of action to the colonies; in America

it was thought to give too little.

The scheme was, moreover, impracticable,

because the desire for union on the part of the several colonies was still

extremely feeble; but it shows on the part of Franklin wonderful

foresightedness. If the Revolution had not occurred, we should probably have

sooner or later come to live under a constitution resembling the Albany plan.

On the other hand, if the Albany plan had been put into operation, it insight

perhaps have so adjusted the relations of the colonies to the British

government that the Revolution would not have occurred.

The only persons that favored Franklin's scheme were

the royal governors, and this was because they hoped it might be of service in

raising money with which to fight the French. In such matters the local

assemblies were extremely niggardly. At the beginning of the war in 1755,

Franklin had been for some years the leading spirit in the assembly of

Pennsylvania, which was engaged in a fierce dispute with the governor

concerning the taxation of the proprietary estates. The governor contended that

these should be exempt from taxation; the assembly insisted rightly that these

estates should bear their one share of the public burdens. On another hotly

disputed question the assembly was clearly in the wrong; it insisted upon

issuing paper money, and against this pernicious folly governor after governor

fought with obstinate bravery. In 1755 the result of these furious contentions

was that Braddock's army was unable to get any support except from the

steadfast personal exertions of Franklin, who used his great influence with the

farmers to obtain horses, wagons, and provisions, pledging his own property for

their payment. Until the question of the proprietary estates should be settled,

the operations of the war seemed likely to be paralyzed.

In 1757 Franklin was sent over to England to plead

the cause of the assembly before the Privy Council. This business kept him in

England five years, in the course of which he became acquainted with the most

eminent people in the country. His discoveries and writings had won him a

European reputation. Before He left England, in 1762, he received the degree of

LL.D. from the universities of Oxford and Edinburgh. His arguments before the Privy

Council were successful; the sorely vexed question was decided against the

proprietary governors; and on his return to Pennsylvania in 1762 he received

the formal thanks of the assembly. It was not long before his services were

again required in England. In 1764 Grenville gave notice of his proposed Stamp Act for defraying part of the expenses

of the late war, and Franklin was sent to England as agent for Pennsylvania,

and instructed to make every effort to prevent the passage of the stamp act.

He carried out his instructions ably and faithfully

; but, when the obnoxious law was passed in 1765, he counseled submission. In

this case, however, the wisdom of this wisest of Americans proved inferior to

the "collective wisdom" of his fellow countrymen.

Warned by the fierce resistance of the Americans, the new ministry of Lord

Rockingham decided to reconsider the act. In an examination before the House of

Commons, Franklin's strong sense and varied knowledge won general admiration,

and contributed powerfully toward the repeal of the stamp act. The danger was

warded off but for a time, however, next year Charles Townshend carried, his

measures for taxing American imports and applying the proceeds to the

maintenance of a civil list in each of the colonies, to be responsible only to

the British government. The need for Franklin's services as mediator was now so

great that he was kept in England, and presently the colonies of Massachusetts,

New Jersey, and Georgia chose him as their agent.

During these years he made many warm friendships

with eminent men in England, as with Burke, Lord Shetburne, Lord Howe, David

Hartley, and Dr. Priestley. His great powers were earnestly devoted to

preventing a separation between England and America. His methods were eminently

conciliatory; but the independence of character with which he told unwelcome

truths made him an object of intense dislike to the king and his friends, who

regarded him as aiming to undermine the royal authority in America. George III is said to have warned his

ministers against”that crafty American, who is more than a match for you

all." In 1774 this dread and dislike found vent in an explosion,

the echoes of which have hardly yet died away. This was the celebrated affair

of the "Hutchinson letters."

For several years a private and unofficial

correspondence had been kept up between Hutchinson, Oliver, and other high

officials in Massachusetts, on the one hand, and Thomas Whately, who had formerly

been private secretary to George Grenville, on the other. The choice of Whately

for correspondent was due to the fact that he was supposed to be very familiar

at once with colonial affairs and with the views and purposes of the king's

friends in these letters Hutchinson had a great deal to say about the weakness

of the royal government in Massachusetts, and the need for a strong military

force to support it ; he condemned the conduct of Samuel Adams and the other

popular leaders as seditious, and enlarged upon the turbulence of the people of

Boston; he doubted if it were practicable for a colony removed by 3,000 miles

of ocean to enjoy all the liberties of the mother country without severing its

connection with her; and he had therefore reluctantly come to the conclusion

that Massachusetts must submit to "an abridgment of what are

called English liberties."

Oliver, in addition to such general views,

maintained that judges and other crown officers should have fixed salaries

assigned by the crown, so as to become independent of popular favor. There can

be no doubt that such suggestions were made in perfect good faith, or that

Hutchinson mid Oliver had the true interests of Massachusetts at heart,

according to their lamentably inadequate understanding of the matter. But to

the people of Massachusetts, at that time, such suggestions could but seem

little short of treasonable.

This point has never been satisfactorily cleared up.

At all events, they were brought to Franklin as containing political

intelligence that might prove important. At this time Massachusetts was

furiously excited over the attempt of Lord North's government to have the

salaries of the judges fixed and paid by the crown instead of the colonial

assembly. The judges had been threatened with impeachment should they dare to

receive a penny from the royal treasury, and at the head of the threatened

judges was Oliver's younger brother, the chief justice of Massachusetts. As

agent for the colony, Franklin felt it to be his duty to give information of

the dangerous contents of the letters now laid before him. Although they

purported to be merely a private and confidential correspondence, they were not

really " of the nature of private letters between friends." As

Franklin said, "they were written by public officers to persons in

public station, on public affairs, and intended to procure public

measures"; they were therefore handed to other public persons,

who might be influenced by them to produce those measures; their tendency was

to incense the mother country against her colonies, and, by the steps

recommended, to widen the breach, which they effected.

The chief caution "from the writers to

Thomas Whately" with respect to privacy was, to keep their

contents from "the knowledge of the colonial agents in

London," who, the writers apprehended, "might return

them, or copies of them, to America." Franklin felt, as

Willingham might have felt on suddenly discovering, in private and confidential

papers, the incontrovertible proof of some popish plot against the life

of Queen Elizabeth. From the person that brought him the letters he got

permission to send them to Massachusetts, on condition that they should be

shown only to a few people in authority, that they should not be copied or

printed, that they should presently be returned, and that the name of the

person from whom they were obtained should never be disclosed.

This last condition was most thoroughly fulfilled. The

others must have been felt to be mainly a matter of form; it was obvious that,

though they might be literally complied with, their spirit would inevitably be

violated. As Orlando Hutchinson writes, “we all know what this sort of

secrecy means, and what will be the end of it"; and, as Franklin

himself observed, "there was no restraint proposed to talking of

them, but only to copying." The letters were sent to the proper

person, Thomas Cushing, speaker of the Massachusetts assembly, and he showed

them to Hancock, Hawley, and the two Adamses.

To these gentlemen it could have been no new discovery that Hutchinson and

Oliver held such opinions as were expressed in the letters; but the documents

seemed to furnish tangible proof of what had long been suspected, that the

governor and his lieutenant were plotting against the liberties of

Massachusetts. They were soon talked about at every town meeting and on every

Street corner. The assembly twitted Hutchinson with them, and asked for copies

of these and other such papers as he might see fit to communicate, He replied,

somewhat sarcastically, ”If you desire copies with a view to make them

public, the originals are more proper for the purpose than any copies."

Mistaken and dangerous as Hutchinson's policy was,

his conscience acquitted him of any treasonable purpose, and he must naturally

have preferred to have the people judge him by what he had really written

rather than by vague and distorted rumors. His reply was taken as sufficient

warrant for printing the letters, and they were soon in the possession of every

reader in England or America who could afford sixpence for a political tract.

On the other side of the Atlantic they aroused as much excitement as on this,

and William Whitely became concerned to know who could have purloined the

letters. On slight evidence he charged a Mr. Temple with the theft, and a duel

ensued in which Whately was wounded. Hearing of this affair, Franklin published

a card in which he avowed his own share in the transaction, and in a measure

screened all others by drawing the full torrent of wrath and abuse upon

himself. All the ill suppressed spleen of the king's friends was at once

discharged upon him.

Meanwhile the Massachusetts assembly formally censured the letters, as evidence of a scheme for subverting the constitution of the colony, and petitioned the king to remove Hutchinson and Oliver from office. In January 1774, the petition was duly brought before the Privy Council in the presence of a large and brilliant gathering of spectators. The solicitor general, David Wedderburn, instead of discussing [he question on its merits, broke out with a violent and scurrilous invective against, Franklin, whom he derided as a man of letters, calling him a "man of three letters," the Roman slang expression for fur, a thief. Of the members of government present, Lord North alone preserved decorum; the others laughed and clapped their hands, while Franklin stood as unmoved as the moon at the baying of dogs. He could afford to disregard the sneers of a man like Wedderburn, whom the king, though fain to use him as a tool, called the greatest knave in the realm. The Massachusetts petition was rejected as scandalous and next day Franklin was dismissed from his office of postmaster general.

They are in error that thinks it was this personal

insult that led Franklin to favor the revolt of the colonies, as they are also

wrong who suppose that his object in sending home the Hutchinson letters was to

stir up dissension. His conduct immediately after passing through this ordeal

is sufficient proof of the unabated sincerity of his desire for conciliation.

The news of the Boston Tea Party arriving

in England about this time, led presently to the acts of April 1774, for

closing the port of Boston and remodeling the government of Massachusetts. The

only way in which Massachusetts could escape these penalties was by

indemnifying the East India company for the tea that had been destroyed; and

Franklin, seeing that the attempt to enforce the new acts must almost

inevitably lead to war, actually went so far as to advise Massachusetts to pay

for the tea, Samuel Adams, on hearing of this, is said to have observed: ”Franklin

may be a good philosopher, but he is a bungling politician."

Certainly in this instance Franklin showed himself

less farsighted than Adams and the people of Massachusetts. The moment had come

when compromise was no longer possible. To have yielded now, in the face of the

arrogant and tyrannical acts of April would have been not only to stultify the

heroic deeds of the patriots in the last December but it would have broken up

the nascent union of the colonies; it would virtually have surrendered them,

bound hand and foot, to the tender mercies of the king. That Franklin should

have suggested such a step, in order to avoid precipitating a conflict, shows

forcibly how anxious he was to keep the peace. He remained in England nearly a

year longer, though many things were done by the king's party to make his stay

unpleasant. During the autumn and winter he had many conversations with persons

near the government, who were anxious to find out how the Americans might be

conciliated without England's abandoning a single one of the wrong positions

that she had taken. This was an insolvable problem, and when Franklin had

become convinced of this he reluctantly gave it up and returned to America,

arriving in Philadelphia on May 5, 1775, to find that the shedding of blood had

just begun.

On the next day the assembly of Pennsylvania

unanimously elected him delegate to the 2nd Continental Congress, then about to

assemble. He now became a zealous supporter of the war, and presently of

the Declaration of Independence. When

congress, in July decided to send one more petition to the king, he wrote a

letter, which David Hartley read aloud in the House of Commons. "If

you flatter yourselves," said Franklin, "with

beating us into submission, you know neither the people nor the country. The

congress will await the result of their last petition."

On July 4, 1776, Congress appointed a three-member committee composed of Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams to design the Great Seal of the United States. Franklin's proposal (which was not adopted) featured the motto: "Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God" and a scene from the Book of Exodus, with Moses, the Israelites, the pillar of fire, and George III depicted as pharaoh. The design that was produced was never acted upon by Congress and the Great Seal's design was not finalized until a third committee was appointed in 1782

A little

more than two years afterward, in December 1777, as parliament sat overwhelmed

with chagrin at the tidings of Burgoyne's surrender, Hartley pulled out

this letter again and up braided the house with it. "You were

then," said he, "confident of having America under your

feet, and despised every proposition recommending peace and lenient

measures."

When this unyielding temper had driven the Americans

to declare their independence of Great Britain, Franklin was one of the

committee of five chosen by congress to draw up a document worthy of the

Occasion. To the document, as drafted by Jefferson, he seems to have

contributed only a few verbal recommendations. The Declaration of Independence

made it necessary to seek foreign alliances, and first of all with England's

great rival, France. Here Franklin's worldwide fame and his long experience of

public life in England enabled him to play a part that would have been

impossible for any other American. He had fifteen years of practice as an

ambassador, and was thoroughly familiar with European polities. In his old days

of editorial work in Philadelphia, with his noble scholarly habit of putting

every moment to some good use, he had learned the French language, with Italian

and Spanish also, besides getting some knowledge of Latin. He was thus

possessed of talismans for opening many a treasure house, and among all the on

eyelopaedist philosophers of Paris it would have been hard to point to a mind

more encyclopedic than his own.

Negotiations with the French court had been begun

already, through the agency of Arthur Lee and Silas Deane, and in the autumn of

1776 Franklin was sent out to join with these gentlemen in securing the active

aid and cooperation of France in the war. His arrival, on December 21st was the

occasion of great excitement in the fashionable world of Paris. Thinkers like

D'Alembert and Diderot regarded him as the embodiment of practical wisdom. To

many he seemed to sum up in himself the excellences of the American cause,

justice, good sense, and moderation. It was Turgot that said of him, "

Eripuit coelo fuhnen, sceptrumque tyrannis." As symbolizing the

liberty for which all France was yearning, he was greeted with a popular enthusiasm

such as perhaps no French man of letters except Voltaire has ever called forth.

Shopkeepers rushed to their doors to catch a glimpse of him as he passed along

the sidewalk, while in evening salons jeweled ladies of the court, vied with

one another in paying him homage. As the first fruits of his negotiations, the

French government agreed to furnish two million lives a year, in quarterly

installments, to aid the American cause. Arms and ammunition were sent over,

and Americans were allowed to fit out privateers in French ports, and even to

bring in and sell their prizes.

Further than this France was not yet ready to go.

She did not wish to incur the risk of war with England until an American

alliance could seem to promise her some manifest advantage. This surreptitious

aid continued through the year 1777, until the surrender of Burgoyne put a new

face upon things. The immediate consequence of that great event was an attempt

on the part of Lord North's government to change front, and offer concessions to

the Americans, which, if they had ever been duly considered, might even at this

late moment have ended in some compromise between England and the United

States. Now, if ever, was the moment for France to interpose, and she seized

it. On 6 February 1778, the treaty was signed at Paris, which ultimately

secured the independence of the United States.

For the successful management of this negotiation,

one of the most important in the annals of modern diplomacy, the credit is

almost solely due to Franklin. Another invaluable service was the negotiation

of loans without which it would have been impossible for the United States to

carry on the war. As the Continental congress had no power to levy taxes, there

were but three ways in which it could pay the expenses of the army: (1) By

requisitions upon the state governments; (2) by issuing its promissory notes,

or so-called "paper money"; (3) by foreign loans.

The first method brought in money altogether too

slowly; the second served its purpose for a short time, but by 1780 the

continental notes had become worthless. The war of independence would have been

an ignominious failure but for foreign loans, and these were made mostly by

France and through the extraordinary sagacity and tact of Franklin. It is

doubtful if any other man of that time could have succeeded in getting so much

money from the French government, which found it no easy matter to pay its own

debts and support an idle population of nobles and clergy upon taxes wrung from

a groaning peasantry.

During Franklin's stay in Paris the annual

contribution of 2,000,000 livres was at first increased to 3,000,000, and

afterward, in 1781, to 4,000,000. Besides this, which was a loan, the French

government sent over 9,000,000 as a free gift, and guaranteed the interest upon

a loan of 10,000,000 to be raised in Holland. Franklin himself, just before

sailing for France, had gathered together all the cash he could command for the

moment, beyond what was needed for immediate necessities, and amounting to

nearly £4,000, and put it into the United States treasury as a loan.

On the fall of Lord North's ministry in March 1782,

Franklin sent a letter to his friend, Lord Shelburne, expressing a hope that

peace might soon be made. When the letter reached London, the new ministry, in

which Shelburne was secretary of state for home and colonies, had already been

formed, and Shelburne, with the consent of the cabinet, replied by sending over

to Paris an agent to talk with Franklin informally, and ascertain the terms

upon which the Americans would make peace. The person chosen for this purpose

was Richard Oswald, a Scottish merchant of frank disposition and liberal views.

In April there were several conversations between Oswald and Franklin, in one

of which the latter suggested that, in order to make a durable peace, it was

desirable to remove all occasion for future quarrel; that the line of frontier

between New York and Canada was inhabited by a lawless set of men, who in time

of peace would be likely to breed trouble between their respective governments;

and that therefore it would be well for England to cede Canada to the United

States. A similar reasoning would apply to Nova Scotia. By ceding these

countries to the United States, it would be possible, from the sale of

unappropriated lands, to indemnify the Americans for all losses of private

property during the war, and also to make reparation to the Tories whose

estates had been confiscated. By pursuing such a policy, England, which had

made war on America unjustly, and had wantonly done it great injuries, would

achieve not merely peace, but reconciliation with America, and reconciliation,

said Franklin, is "a sweet word."

This was a very bold tone for Franklin to take: but

he knew that almost every member of the Whig ministry had publicly expressed

the opinion that the war against America was unjust and wanton; and being,

moreover, a shrewd hand at a bargain, he began by setting his terms high.

Oswald seems to have been convinced by Franklin's reasoning, and expressed

neither surprise nor reluctance at the idea of ceding Canada. The main points

of this conversation were noted upon a sheet of paper, which Franklin allowed

Oswald to take to London and show to Lord Shelburne, first writing upon it an

express declaration of its informal character. On receiving this memorandum,

Shelburne did not show it to the cabinet, but returned it to Franklin without

any immediate answer, after keeping it only one night. Oswald was presently

sent back to Paris, empowered as commissioner to negotiate with Franklin, and

carried Shelburne's answer to the memorandum that desired the cession of Canada

for three reasons. The answer was terse: "1. By way of reparation.

Answer: No reparation can be heard of. 2. To prevent future wars. Answer: it is

to be hoped that some more friendly method will be found. 3. As a fund of

indemnification to loyalists. Answer:

No independence to be acknowledged without their being taken care

of." Besides, added Shelburne, the Americans would be

expected to make some compensation for the surrender of Charleston, Savannah,

and the City of New York, still

held by British troops.

From this it appears that Shelburne, as well as Franklin, knew how to begin by asking more than he was likely to get. England was no more likely to listen to a proposal for ceding Canada than the Americans were to listen to the suggestion of compensating the British for surrendering New York. But there can be little doubt that the bold stand thus taken by Franklin at the outset, together with the influence he acquired over Oswald, contributed materially to the brilliant success of the American negotiations. This is the more important to be noted in connection with the biography of Franklin, since in the later stages of the negotiations the initiative passed almost entirely out of his hands, and into those of his colleagues, Jay and Adams. The form that the treaty took was mainly the work of these younger statesmen; the services of Franklin were chiefly valuable at the beginning, and again, to some extent, at the end.

There were two grave difficulties in making a

treaty. The first was, that France was really hostile to the American claims.

She wished to see the country between the Alleghenies and the Mississippi divided

between England and Spain; England to have the region north of the Ohio, and

the region south of it to remain an Indian territory under the protectorate of

Spain, except a narrow strip on the western slope of the Alleghenies, over

which the United States might exercise protectorship. In other words, France

wished to confine the United States to the east of the Alleghenies, and forever

prevent their expansion westward. France also wished to exclude the Americans

from all share in the fisheries, in order to prevent the United States from

becoming a great naval power. As France, up to a certain point, was our ally,

this antagonism of interests made the negotiation extremely difficult. The

second difficulty was the unwillingness of the British government to

acknowledge the independence of the United States as a condition that must

precede all negotiation. The Americans insisted upon this point, as they had

insisted ever since the Staten Island conference in 1776; but England wished to

withhold the recognition long enough to bargain with it in making the treaty.

This difficulty was enhanced by the fact that, if this point were conceded to

the Americans, it would transfer the conduct of the treaty from the colonial

secretary, Shelburne, to the foreign secretary, Fox; and these two gentlemen

not only differed widely in their views of the situation, but were personally

bitter enemies.

Presently Fox heard of the private memorandum that

Shelburne had received from Franklin but had not shown to the cabinet, and he

concluded, quite wrongly, that Shelburne was playing a secret part for purposes

of his own. Accordingly, Fox made up his mind at all events to get the American

negotiations transferred to his own department; and to this end, on the last

day of June he moved in the cabinet that the independence of the United States

should be unconditionally acknowledged, so that England might treat as with a

foreign power. The motion was lost, and Fox prepared to resign his office; but

the very next day the death of Lord Rockingham broke up the ministry. Lord

Shelburne now became prime minister, and other circumstances occurred which

simplified the problem, in April the French fleet in the West Indies had been

annihilated by Rodney; in September this was followed by the total defeat of

the combined French and Spanish forces at Gibraltar. This altered the situation

seriously.

England, though defeated in America, was victorious

as regarded France and Spain. The avowed object, for which France had entered

into alliance with the Americans, was to secure the independence of the United

States, and this point was now substantially gained. The chief object for which

Spain had entered into alliance with France was to drive the English from

Gibraltar, and this point was now decidedly lost. France had bound herself not

to desist from the war until Spain should recover Gibraltar; but now there was

little hope of accomplishing this, except by some fortunate bargain in the

treaty. Vergennes now tried to satisfy Spain at the expense, of the United

States, and he sent a secret emissary under an assumed name to Lord Shelburne,

to develop his plan for dividing the Mississippi valley between England and

Spain. This was discovered by Jay, who counteracted it by sending a messenger

of his own to Shelburn who thus perceived the antagonism that had arisen

between the allies.

It now became manifestly for the advantage of England

and the United States to carry on their negotiations without the intervention

of France, as England preferred to make concessions to the Americans rather

than to the house of Bourbon. By first detaching the United States from the

alliance, she could proceed to browbeat France and Spain. There was an obstacle

in the way of a separate negotiation. The chevalier Luzerne, the French

minister at Philadelphia, had been busy with congress, and that body had sent

instructions to its commissioners at Paris to be guided in all things by the

wishes of the French court. Jay and Adams, overruling Franklin, took the

responsibility of disregarding these instructions; and the provisions of the

treaty, so marvelously favorable to the Americans, were arranged by a separate negotiation

with England.

In the arrangement of the provisions, Franklin

played an important part, especially in driving the British commissioners from

their position with regard to the compensation of loyalists. After a long

struggle upon this point, Franklin observed that, if the loyalists were to be

indemnified, it would be necessary also to reckon up the damage they had done

in burning villages and shipping, and then strike a balance between the two

accounts" and he gravely suggested that a special commission might be

appointed for this purpose. It was now getting late in the autumn, and

Shelburne felt it to be a political necessity to bring the negotiation to an

end before the assembling of parliament. At the prospect of endless discussion,

which Franklin's suggestion involved, the British commissioners gave way and

accepted the American terms. Affairs having reached this point, it remained for

Franklin to lay the matter before Vergennes in such wise as to avoid a rupture

of the cordial relations between America and France. It was a delicate matter,

for, in dealing separately with the English government, the Americans laid them

open to the charge of having committed a breach of diplomatic courtesy; but

Franklin managed it with entire success.

On the part of the Americans the treaty of 1783 was

one of the most brilliant triumphs in the whole history of modern diplomacy.

Had the affair been managed by men of ordinary ability, the greatest results of

the Revolutionary war would probably have been lost; the new republic would

have been cooped up between the Atlantic and the Alleghenies; our westward

expansion would have been impossible without further warfare; and the formation

of our Federal union would doubtless have been effectively hindered or

prevented. To the grand triumph the varied talents of Franklin, Adams, and Jay alike contributed. To the latter is due the

credit of detecting and baffling the sinister designs of France; but without

the tact of Franklin this probably could not have been accomplished without

offending France in such wise as to spoil everything.

Franklin's last diplomatic achievement was the

negotiation of a treaty with Prussia, in which was inserted an article looking

toward the abolition of privateering. This treaty, as Washington observed

at the time, was the most liberal that had ever been made between independent

powers, and marked a new era in international morality. In September 1785,

Franklin returned to America, and in the next month was chosen president of

Pennsylvania. The office of president was analogous to the modern position of governor. He held that office for slightly over three years, longer than any other, and served the constitutional limit of three full terms. Shortly after his initial election he was reelected to a full term on October 29, 1785, and again in the fall of 1786 and on October 31, 1787. Officially, his term concluded on November 5, 1788, but there is some question regarding the de facto end of his term, suggesting that the aging Franklin may not have been actively involved in the day-to-day operation of the council toward the end of his time in office.

In May 1787 he was a delegate to the immortal convention that framed the Constitution of the United States. He took a comparatively small part in the debates, but some of his suggestions were very timely, as when he seconded the Connecticut compromise. At the close of the proceedings he made a short speech, in which he said: "I consent, to this constitution, because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best."

Benjamin Franklin died at his home in Philadelphia on April 17, 1790, at age 84. Approximately 20,000 people attended his funeral. He was interred in Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia. In 1728, aged 22, Franklin wrote what he hoped would be his own epitaph:

The Body of B. Franklin Printer; Like the Cover of an old Book, Its Contents torn out, And stript of its Lettering and Gilding, Lies here, Food for Worms. But the Work shall not be wholly lost: For it will, as he believ'd, appear once more, In a new & more perfect Edition, Corrected and Amended By the Author

Chart Comparing Presidential Powers

of America's Four United Republics - Click Here

of America's Four United Republics - Click Here

United Colonies and States First Ladies

1774-1788

United Colonies Continental Congress

|

President

|

18th Century Term

|

Age

|

Elizabeth "Betty" Harrison Randolph (1745-1783)

|

09/05/74 – 10/22/74

|

29

| |

Mary Williams Middleton (1741- 1761) Deceased

|

Henry Middleton

|

10/22–26/74

|

n/a

|

Elizabeth "Betty" Harrison Randolph (1745–1783)

|

05/20/ 75 - 05/24/75

|

30

| |

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

05/25/75 – 07/01/76

|

28

| |

United States Continental Congress

|

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

07/02/76 – 10/29/77

|

29

| |

Eleanor Ball Laurens (1731- 1770) Deceased

|

Henry Laurens

|

11/01/77 – 12/09/78

|

n/a

|

Sarah Livingston Jay (1756-1802)

|

12/ 10/78 – 09/28/78

|

21

| |

Martha Huntington (1738/39–1794)

|

09/29/79 – 02/28/81

|

41

| |

United States in Congress Assembled

|

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

Martha Huntington (1738/39–1794)

|

03/01/81 – 07/06/81

|

42

| |

Sarah Armitage McKean (1756-1820)

|

07/10/81 – 11/04/81

|

25

| |

Jane Contee Hanson (1726-1812)

|

11/05/81 - 11/03/82

|

55

| |

Hannah Stockton Boudinot (1736-1808)

|

11/03/82 - 11/02/83

|

46

| |

Sarah Morris Mifflin (1747-1790)

|

11/03/83 - 11/02/84

|

36

| |

Anne Gaskins Pinkard Lee (1738-1796)

|

11/20/84 - 11/19/85

|

46

| |

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (1747-1830)

|

11/23/85 – 06/06/86

|

38

| |

Rebecca Call Gorham (1744-1812)

|

06/06/86 - 02/01/87

|

42

| |

Phoebe Bayard St. Clair (1743-1818)

|

02/02/87 - 01/21/88

|

43

| |

Christina Stuart Griffin (1751-1807)

|

01/22/88 - 01/29/89

|

36

|

Constitution of 1787

First Ladies |

President

|

Term

|

Age

|

April 30, 1789 – March 4, 1797

|

57

| ||

March 4, 1797 – March 4, 1801

|

52

| ||

Martha Wayles Jefferson Deceased

|

September 6, 1782 (Aged 33)

|

n/a

| |

March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817

|

40

| ||

March 4, 1817 – March 4, 1825

|

48

| ||

March 4, 1825 – March 4, 1829

|

50

| ||

December 22, 1828 (aged 61)

|

n/a

| ||

February 5, 1819 (aged 35)

|

n/a

| ||

March 4, 1841 – April 4, 1841

|

65

| ||

April 4, 1841 – September 10, 1842

|

50

| ||

June 26, 1844 – March 4, 1845

|

23

| ||

March 4, 1845 – March 4, 1849

|

41

| ||

March 4, 1849 – July 9, 1850

|

60

| ||

July 9, 1850 – March 4, 1853

|

52

| ||

March 4, 1853 – March 4, 1857

|

46

| ||

n/a

|

n/a

| ||

March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865

|

42

| ||

February 22, 1862 – May 10, 1865

| |||

April 15, 1865 – March 4, 1869

|

54

| ||

March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877

|

43

| ||

March 4, 1877 – March 4, 1881

|

45

| ||

March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881

|

48

| ||

January 12, 1880 (Aged 43)

|

n/a

| ||

June 2, 1886 – March 4, 1889

|

21

| ||

March 4, 1889 – October 25, 1892

|

56

| ||

June 2, 1886 – March 4, 1889

|

28

| ||

March 4, 1897 – September 14, 1901

|

49

| ||

September 14, 1901 – March 4, 1909

|

40

| ||

March 4, 1909 – March 4, 1913

|

47

| ||

March 4, 1913 – August 6, 1914

|

52

| ||

December 18, 1915 – March 4, 1921

|

43

| ||

March 4, 1921 – August 2, 1923

|

60

| ||

August 2, 1923 – March 4, 1929

|

44

| ||

March 4, 1929 – March 4, 1933

|

54

| ||

March 4, 1933 – April 12, 1945

|

48

| ||

April 12, 1945 – January 20, 1953

|

60

| ||

January 20, 1953 – January 20, 1961

|

56

| ||

January 20, 1961 – November 22, 1963

|

31

| ||

November 22, 1963 – January 20, 1969

|

50

| ||

January 20, 1969 – August 9, 1974

|

56

| ||

August 9, 1974 – January 20, 1977

|

56

| ||

January 20, 1977 – January 20, 1981

|

49

| ||

January 20, 1981 – January 20, 1989

|

59

| ||

January 20, 1989 – January 20, 1993

|

63

| ||

January 20, 1993 – January 20, 2001

|

45

| ||

January 20, 2001 – January 20, 2009

|

54

| ||

January 20, 2009 to date

|

45

|

Capitals of the United Colonies and States of America

Philadelphia

|

Sept. 5, 1774 to Oct. 24, 1774

| |

Philadelphia

|

May 10, 1775 to Dec. 12, 1776

| |

Baltimore

|

Dec. 20, 1776 to Feb. 27, 1777

| |

Philadelphia

|

March 4, 1777 to Sept. 18, 1777

| |

Lancaster

|

September 27, 1777

| |

York

|

Sept. 30, 1777 to June 27, 1778

| |

Philadelphia

|

July 2, 1778 to June 21, 1783

| |

Princeton

|

June 30, 1783 to Nov. 4, 1783

| |

Annapolis

|

Nov. 26, 1783 to Aug. 19, 1784

| |

Trenton

|

Nov. 1, 1784 to Dec. 24, 1784

| |

New York City

|

Jan. 11, 1785 to Nov. 13, 1788

| |

New York City

|

October 6, 1788 to March 3,1789

| |

New York City

|

March 3,1789 to August 12, 1790

| |

Philadelphia

|

December 6,1790 to May 14, 1800

| |

Washington DC

|

November 17,1800 to Present

|

Historic.us

A Non-profit Corporation

202-239-1774 | Office

A Non-profit Corporation

Primary Source Exhibits

727-771-1776 | Exhibit Inquiries

202-239-1774 | Office

Website: www.Historic.us